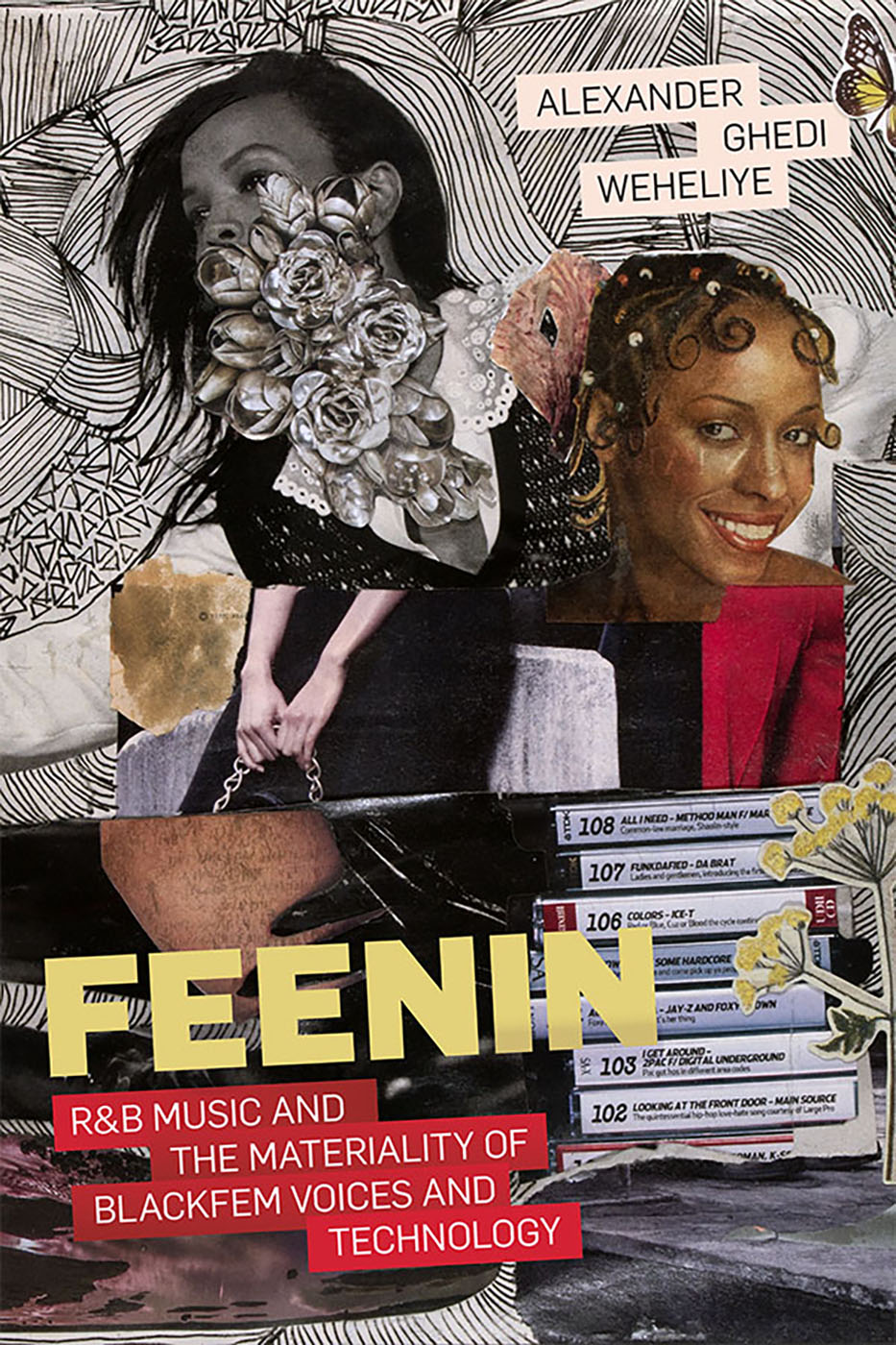

Weheliye argues for the centrality of R&B in discussions about Black music; rather than acquiescing to claims that R&B is “dead” or apolitical, he reveals R&B music to be a key site of cultural analysis to understand Black life in our current moment. In this conversation, arman and Weheliye discuss what he hopes readers take away from Feenin, the transformation of music platforms, and the current landscape of R&B, and the writing styles of SZA and Frank Ocean.

Alexander Weheliye is Malcom S. Forbes Professor of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. Weheliye teaches and researches in the areas of critical theory, Black literature and culture, gender and sexuality studies, social technologies, and popular culture. He is the author of Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity (2005), and Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (2014). Feenin' will release Fall 2023 with Duke University Press.

zuri arman: Can you talk about how you hope people receive Feenin? Where do you see the book in relation to current discourses in Black studies, sonic studies, and Black music? How do you see it functioning in the current moment of music in general?

Alexander Weheliye: What I would really like to see is other folks taking up R&B music, broadly defined, as a sphere for critical reflection on Black music and, by extension, Black life. That’s my hope for R&B because I feel that it doesn't really get enough critical attention. I also think the book contributes to broader conversations in Black studies in terms of thinking about the kinds of places of labor, violence, the intimate sphere, etc., which are all things I think that are put on the table–both sonically and lyrically–by R&B music.

zuri arman: Given that the book takes the form of an album, I was thinking about the different forms of music compilation: the album, the mixtape, and the playlist. Could you say how you've seen these different forms impact how listeners engage with music in your experience over the years?

Alexander Weheliye: I think all those things have had a huge influence in terms of how people engage in music. In the contemporary moment, there is a de-emphasis on the album with a few notable exceptions. The playlist has taken over. It also needs to be said that oftentimes the playlist—especially with the large commercial streamers—has some kind of human input but oftentimes it's AI-generated.

But that's where listening is going. And I think in some ways that's too bad. But, in other ways, I also remember the time where if you liked a song you had to buy the album, the tape, or the CD–even if you only liked one song. You had to pay somewhere between $12 and $18—the cost in the late 1980s, early 1990s, and the early 2000s. So, if you look at the history of the music industry, the album was really a boon for it. And one of the things that I've also been thinking about more recently is how, in the early 2000s, which was the heyday where NSYNC would sell 2 million albums the first week of release…one of the things the recording industry stopped doing, for instance, is produce commercially available syncs. Initially, they weren't counted on the Billboard chart. But then, Billboard changed so you could have an album track be a number one hit that was never released as a CD single. This is the recording industry in its last moment of gasping where it was selling a lot of things, but it was also really clear that with the online “illegal” distribution of music, things were about to change as well.

The way I knew [the mixtape] was something that you did privately. You recorded from a CD or Vinyl; you put together a selection of songs. Sometimes, back in the day people would also record from the radio so you could hear your favorite songs. And then you get to the 1990s, and it becomes de rigueur—particularly for hip-hop DJs initially in New York—to have these unofficially released mixtapes where they mix the hottest tracks of the day. Similar things happen in electronic dance music, house, jungle, etc. Then, at a certain point, those become commercially available. Before that, these were just unofficial things sold on street corners. And once they become commercially available, they really change their format.

At this point in time, I really don't understand what the distinction between an album and a mixtape is. It’s really moved so far into another direction where it's basically a mixtape if the office and the record company tell us it's a mixtape. And I don't quite understand…even when it took off in hip-hop as its own thing it was artists like Lil’ Wayne rapping over other people's beats that they couldn't officially release because of licensing reasons. But you could buy the tape and download it somewhere later. And now even that has disappeared. It just seems to be a format like an album.

I think all those things really shape how we engage as listeners with music. Not necessarily in a good or bad way. I think there are limitations to all those things. In some ways, we have the most choice as listeners at this point in time but, in other ways, that choice is also really limited. Because, for instance, so much of the history of dance music is not on Spotify or Tidal. Maybe if you're lucky something will be on Soundcloud or YouTube, but so much of it is not on there. I’m not even talking about super obscure stuff. But that, too. There’s just so many remixes of major house artists from the 1990s that are nowhere to be found on the streaming services. All these formats enable us to engage with music and sound differently. But they also usually come with certain kinds of limitations. With streaming too: if it's taken off streaming, it's not there for you anymore. You don't own it, whereas I can go somewhere deep dark into my basement and dig up a CD that I bought in 1994 if I want to listen to it.

zuri arman: Could you describe the current moment of R&B? How do you see the landscape right now?

Alexander Weheliye: (Chuckling) It's a little desolate overall, I would say. It's definitely not the late 1990s and the early 2000s where R&B music was number one on the pop charts every week. I think R&B was the genre hit the hardest by the move to streaming because it really destroyed the ecosystem of Black record stores, Black radio stations, and certain kinds of performance venues that specialize in Black music. And record companies had Black music sections as part of the company, which is hella problematic and comes from segregation, but there was infrastructure and money. I think that infrastructure and money has been taken away from R&B music, and you can tell.

The other thing that has happened is the church used to be the training ground for a lot of R&B singers and musicians. It still exists, but overall it's not the path anymore. If you look at most of the successful R&B artists in the contemporary moment like Brent Faiyaz, Frank Ocean, and Jhené Aiko, none of them have any church training—at least not that I know of.

And then I think R&B music has become more of “vibe music.” I’m not saying that in a derogatory way. I think that it's become more open to a certain kind of ambiance. And I think that might also have something to do with the playlisting, especially Spotify where playlists are things that work well in the background at the barbershop, the nail shop, etc. It's something new, but I also think about it in relationship to the rise of quiet storm in the 1980s, which was very similar. You had these very long, meandering songs. It was all very soft. I was actually going back and reading some feedback to quiet storm and a lot of people had the same critique. They had the same critique of Sade as they do with SZA now. It’s like, “this is just background music…She can't really sing…” even though a lot of people loved and still love Sade. But there was this idea that this [music] was not grounded, authentic, etc. Even with Luther Vandross, [there were] a lot of critiques of how his music and his voice were too slick.

I would also say that hip-hop takes on all these different parts of R&B. If you look at all the rappers…I don't actually pay that much attention to mainstream hip-hop—especially the dudes (chuckles). I kind of checked out a couple of years ago…a lot of them do this vocalization that's not necessarily singing but it's also not rapping like the 1980s, the 1990s, and even the early 2000s. So, I think a lot of R&B was ingested by hip-hop. Of course, hip-hop also influences R&B music. R&B singing becomes more like rapping and there's this back and forth. And one of the things I've seen recently is [that] a lot of R&B singers are also really amazing rappers where that distinction doesn't really happen as much.

Things change, right? Hip-hop has changed. All musical genres have continually changed. One of the things that I really wanted to do with Feenin is to not engage with R&B music in that mode…that it's only declining or dead and doesn't mean anything to Black people anymore. It might mean something different than it did in 1965, but I still think this is something that Black people–particularly Black women [and] Black queer folks–really live for and engage with in a very, very deep way. It's just not as obvious as it might be with certain other genres.

I think R&B is in a really interesting place. I'm looking forward to seeing where things go. One of the other things that happens…I felt like in the 1990s [there] was a moment where white performers started to embody the guttural, melismatic Black singing styles. Think of someone like Céline Dion. I'm not saying that Céline Dion ever actually sounded Black (chuckles), but she embraced that. Then you've got Christina Aguilera and a lot of those artists. And then I think Black artists, at a certain point, were just like, “Oh white people are doing that now. We need to move in a different direction.” And I think that's what oftentimes happens. I do think R&B is neglected in terms of the infrastructure, but it has so much influence on popular music, right? You listen to Afrobeat [and] so much of it is R&B. You listen to country music and so much sounds like R&B.

zuri arman: Lastly, I just wanna know your thoughts on SZA’s latest album and her transition from Ctrl to SOS.

Alexander Weheliye: I love it a lot. I've listened to it over and over again.

zuri arman: Everybody has. (chuckles)

Alexander Weheliye: It's one of those things where I don't love it as much as Ctrl, but whenever a song comes on and I’m not listening to it I still know every word.

zuri arman: Yeah!

Alexander Weheliye: I think that that's really what makes her such an amazing artist. She’s so hyper-specific in a way that R&B music used to not be. R&B used to traffic in generalities. And again, this is not judgment. It just used to be a different era. And this is my point in Feenin, particularly about SZA and Frank Ocean. They really brought into R&B a kind of observational “singer/ songwriter” mentality–this everyday-ness where it's very specific that this is about SZA, but it's also applicable to so many different people. If we look at the success of that album, it's not only Black people that are buying that album. And there have been some complaints about the tour saying, “Oh my god, there's so many white audiences now.”

zuri arman: I have been shocked by how many… like I’ll be in my Uber and a white guy puts on SZA and I’m like, “Since when were white people listening to SZA?”

Alexander Weheliye: It’s happened over the last five years. I'm not quite as surprised. I'm surprised at the amount, but not that this has actually happened. There were a few moments when I was somewhere and there's all these white people that are singing along to “Broken Clocks” or something. She has that gift of being hyper-specific but also generalizable, and I think that's usually not a place that Black artists get to occupy. I think if you listen to a lot of SZA and Frank Ocean's lyrics, they're specifically about them but they're still relatable, and I think it’s a really interesting place for artists like that to be.

I'm not saying this in terms of quality of music, but I think that SZA occupies a similar territory as an Adele or Taylor Swift at this point. But she does so while her music is still unmistakably Black. There's nothing on that album that’s not Black as fuck. The same thing with Frank Ocean. A lot of times it's not necessarily about them saying this is Black or pro-Black. It's just about their voices. It's how they approach things. It's about their stories…even the songs that are pop-punk, indie rock, or country on the album…because they're sung by SZA and produced by her, and her collaborations [they] still sound unmistakably Black. It'll be interesting to see where she goes from this. If you look at Beyonce's career, it was also unmistakably Black, but it was very non-specific for most of the early parts of her career. This could be about anyone. I think starting with Beyoncé and then going into Lemonade it's become more personalized. It's specifically about Beyoncé but, again, also generalizable. I think that SZA has always maintained that in the same way as Frank Ocean, and from the very beginning. They've become successful with that, whereas I think most other Black artists up to them have to—even if they didn't do it consciously—go to this more general area in terms of their particular lyrics.

Even with someone like Prince, people talked about how he wanted to, with “Purple Rain,” write this arena rock anthem. And there's nothing wrong with that. It's a great song. It's still Black music. But there was a conscious effort where he was like, “Okay, I need to have this crossover ballad that Black radio will play, but that the rock stations will play,” because they were not playing him initially. And I think because we're in a different era—and radio is not a gatekeeper—it's really allowed folks like SZA and Frank Ocean to shine. I'm with that.

zuri arman: I think SZA is done after this. I think that she, just from what I've been picking up, has a lot of frustrations about the music industry. Which leads me to like Ari Lennox because I felt like from her album Shea Butter Baby, which I love…bought it on vinyl, to Age/Sex/Location, she definitely moved from the personal to the generalizable in a way that I didn’t realize until you said this right now. That's why it didn’t really connect with me as much.

Alexander Weheliye: And I think with some artists you see that struggle. Another artist where you really see that is Jasmine Sullivan who came up in an earlier era. Then, with her last album, I just felt like, “Yeah, it's nice that you're getting specific.” But I’m also like, “Why are you doing this?” You know what I’m saying? And again, this is not judgmental or moral in any kind of way. I’m not mad at it. And clearly, it's worked for her because people have been a lot more receptive to her music. But I also wonder what this means for her artistry.

And SZA is gonna come back in 5 years.

zuri arman: I hope so.