CW: The following contains discussions of sexual violence, trauma, and abuse against Black women in carceral systems.

Mass incarceration defines contemporary America; With only 4.2% of the world’s population, the United States holds 20% of the global prison population. The current judicial system is a direct iteration of the violent policing that has targeted Black people since slavery and continues to single them out. Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at nearly five times the rate of white Americans. The prison industrial complex allows the country to benefit economically from incarcerating Black people, and has increasingly criminalized Black women due to a recent focus on nonviolent crimes that statistically happen more frequently in economically disadvantaged communities of color. Black women are only 13% of the country’s women, but they make up 30% of the women in prison and 44% of the women in jail. Many of these women have been imprisoned for acts of self-defense, sex work, minor infractions like shoplifting diapers, or otherwise finding ways to survive in a country that has oppressed them since its founding. Their mistreatment follows them into prisons, where they continue to face mental and sexual abuse. In order to end these cycles of harm, prison abolitionists are actively fighting to dismantle our prison and policing systems. Their demands are for radical freedom, mutual accountability, and safety and security for all people without the threat of violence. As prison abolitionists continue to seek justice and healing outside of carceral structures, there is a need for Black women to receive adequate support within the broken system.

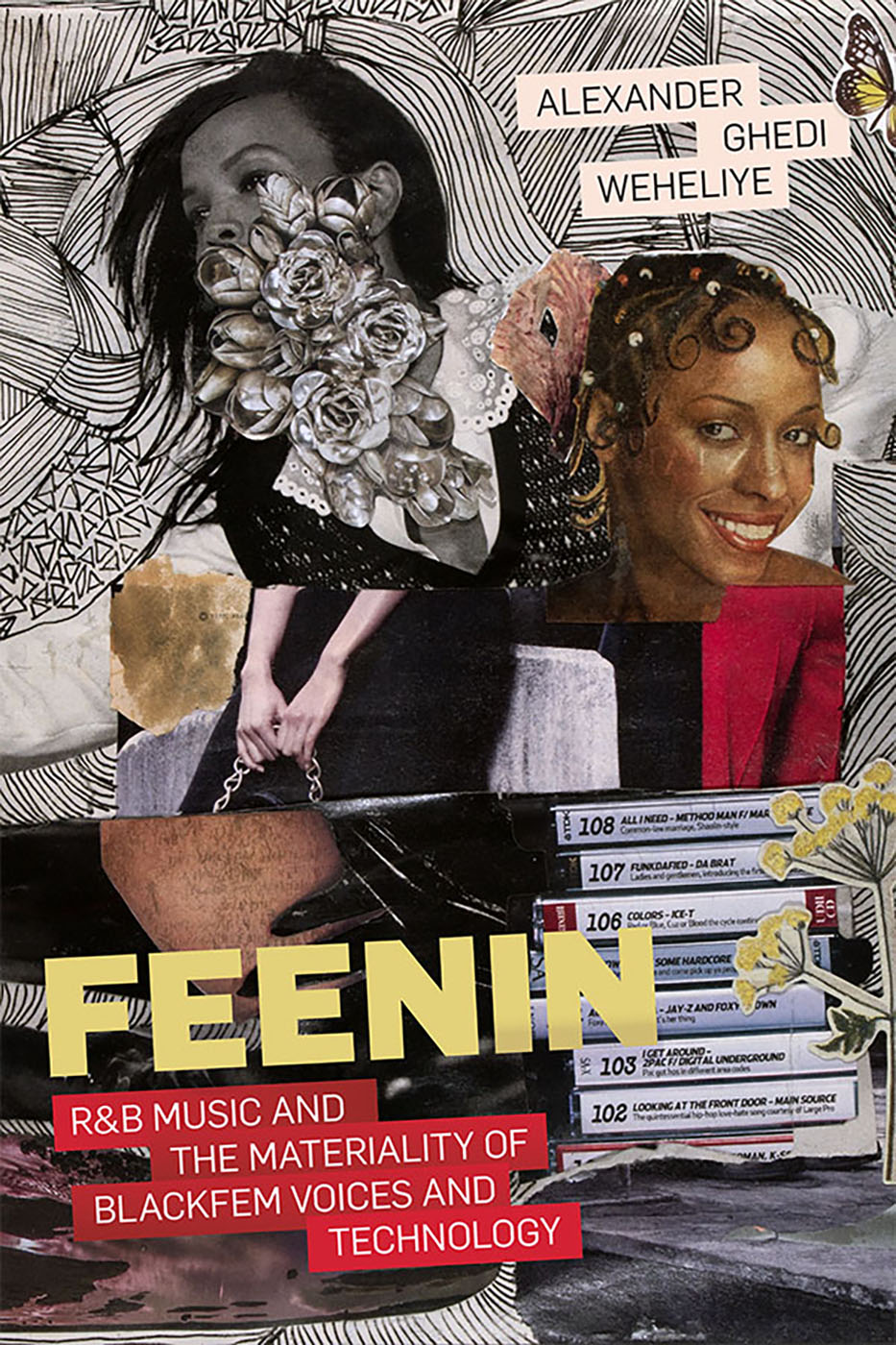

Performance art can help center incarcerated Black women’s voices, promote healing, and expose the realities of the U.S. prison system. Through movement and expression, Black incarcerated women are building their own communities to resist the dehumanization and dismissal of their stories. Actress, playwright, performance art scholar, and Brown University Assistant Professor of the Arts and Africana Studies Dr. Lisa Biggs (she/her) envisions the abolition of oppressive spaces while using artistic practices to amplify the voices of women within the system and prioritize their healing. For her recently published book, The Healing Stage: Black Women, Incarceration, and the Art of Transformation (2022), she worked directly with incarcerated women across four prisons to investigate urgent questions in abolitionist thought and performance art: How can artists and activists seek abolition within carceral institutions? How can we listen to and implement the changes that incarcerated Black women actually want and need? Her work is unapologetically insistent about fighting for Black women’s rights in a way that instigates a cultural and systemic shift towards radical care. She shares her reflections on the current state of incarceration and the potential for the growing population of incarcerated Black women to be granted humanity and justice in a country that has continued to leave Black women behind.

Imani: Why have you chosen to focus on performance art in your academic and artistic life, and what aspects of your personal journey led you to performance art?

Biggs: Like a lot of performers, I was actually a super shy kid. I found a community of other equally shy, awkward kids in theater programs as a middle school and high school student. And it was there, through those theater programs, that I really began to step into a sense of myself that was bigger than the story that I had been telling myself or had been told about what I was capable of as a little Black girl on the south side of Chicago in the eighties and nineties. Those lessons about presence and voice and the importance of storytelling continued for me through college.

I have a B.A. in theater and dance from Amherst College. I worked as an actor in a regional theater but, later on, decided that I wanted more than to go to auditions and get work from other people. When I was an undergrad, I started making my own work. One route that was available to me was to work as a teaching artist, and I eventually landed a job in Washington, DC, at a place called the Living Stage Theatre. It was a multi-generational interracial theatre program right off of U Street, the historic black Broadway in Washington, DC. We made original work with people every day about the most pressing issues on their minds. Living Stage was really born out of a practice of the Black Power and Black Arts movement in the 1960s. Although we were an interracial multi-generational company, it was those kinds of visions that we were thinking about when we got there in the nineties. How do we create new ways of being in the world that are grounded in everyday people’s experiences? I have never stopped asking those questions. I refuse to create a distinction between the academic, the scholarship, and the research in my artistic practice. One can also use our language to think about theater or other forms of performance as a method of research and as an analysis of other areas of human life.

Imani: You believe in the power of performance art, which you explore throughout The Healing Stage: Black Women, Incarceration, and the Art of Transformation (2022). Throughout your research, what affirmed or challenged your existing feelings about performance? Why is performance a healing tool for abolitionists?

Biggs: A lot of theater people—and artists in general—think of our artistic work as a healing practice in that it’s so life-affirming. When I was at Living Stage, we worked with a group of women who were in a comprehensive drug and alcohol recovery program as an alternative to corrections. They were overwhelmingly low-income women of color, trauma survivors, and they are folks who, to survive poverty and deal with pain and suffering, had a history of problematic substance use. They came to Living Stage because something that their site could not do was create a space for them to investigate their voices through artistic practices that were not constantly monitored or evaluated by clinical staff. We were not therapists. We’re not trying to be therapists. However, we understood that storytelling is essential to a healing practice. They were superb artists, and they had been trained in anti-oppression and anti-violence work. They were Black Feminist playwrights.

From my experience, I at first did not understand how we were going to heal using theater in a carceral facility. So that’s what I decided to try to understand—how is this work healing? Naming and performing are part of that process. And that is what theater people are excellent at doing, that process. I’m a prison abolitionist. This single-handedly will not end the criminal legal system as we know it. It will not free anybody from the carceral system. It will not end poverty. But if we never talk about what’s going on, if we never name it, then we can’t do anything about it. And what’s often missing from conversations about policing and about the criminal legal system, about prisons, jails, public health, healing, domestic violence, and sexual assault, are the voices of black women who are criminalized survivors. It is a reductive story to say that they are worthless, they have nothing to share, and that their behavior is just proof of their valuelessness. They were trying to figure out a better way of being in the world. No one wants to live in deep pain. No one does.

Imani: You talk a lot about performance art being a way to affirm oneself. It’s an uplifting practice and serves as a way to build a positive sense of self after years of belittlement and oppression. How can one advocate for the abolition of a carceral system while also fighting for the programs that are uplifting these women within that system? What does that look like?

Biggs: I don’t think of abolition as a magic wand. I think of abolition as a process of undoing. Just as the criminal legal system was established in our country over hundreds of years, it may take some time to undo it—[with] my model of abolition—and it’s even taken a while to come to this. But where I’m sitting right now is a model inspired by Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Mariame Kaba, and adrienne maree brown.

What people have done in the past is create alternative ways of being in the world and living in them. What do I mean by that? My best example right off the top of my head is if you think about what it took to abolish slavery. What we often think about is Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. “Whoo! Yes, people are free.” But that’s not what happened. Getting him to truly abolish slavery, that takes Frederick Douglass all up in his ear. That’s Elizabeth Keckley, his wife’s dressmaker, all up in people’s ears. That is generations of black—and some white—abolitionists storming the country, writing letters. trying to convince prominent people that they should pass some new laws. So enslaved people were freeing themselves. They were creating new modalities, and they were teaching them to each other because they fundamentally believed that slavery is not permanent, long-lasting, or inescapable.

One of the first things that your abuser tells you is that you’re the only one, and you better not talk about it. People think they are the only ones, and what facilitators of theater and dance programs for women who are incarcerated know when they walk into the building is that everybody is a survivor. The only people who do not know that they are survivors are the women themselves because they were all told that they’re the only ones. Can you imagine what happens when one person is brave enough to disclose through a poem or a song that they are survivors, when people realize they are not alone?

Part of a healing process is ending feelings of isolation and shame and fear. They don’t have to tell trauma survival stories. That’s terrible theater, and no one is asking that. We might, though, ask something like, “Bring in a photo of a picket fence and some flowers.” Then say, “Can you write a poem or a story that’s inspired by this? Or in response to this?” What we’ve learned over time is that there usually is one person in a room who needs to tell a story about surviving. Not necessarily all the graphic details about what happened, but they need to tell, and it does not matter what the prompt is. That is the story that incarcerated women want to tell. It’s killing them. And so they want to give it voice, and what they realize after coming back to class week after week is that they can be seen, heard, understood, and—most importantly—be believed. In a theater program! Who knew, right? That doesn’t seem to make any kind of sense. But the women who I worked with, they’re not doing Shakespeare. They’re creating platforms for women to tell their own stories and are insisting on the value of those stories.

Imani: You write in The Healing Stage that correction art programs provide “one of the few spaces in which incarcerated people can (re)present themselves to society.” What is your answer to people who struggle to understand how art programs provide healing?

Biggs: Well, you know, the book. (Chuckles) The book is my evidence. It’s fifteen years’ worth of research at three facilities in the United States and one in South Africa. And it’s their work. The overwhelming majority of people I met were involved in shoplifting, sex work, and criminal drug use because they wanted to escape the kind of life that they were in. We have criminalized what they have done to survive. So, in the absence of other support, they are running to theater programs. Running and fighting for them. They’re the longest existing programs outside of the church programs in these facilities. And why? Because women want to do this work and they want to do it now. They’re not going to wait until they’re close to parole to be able to maybe get into a program when they only have two years to go on a fifteen, twenty, or fifty-year sentence, right? What do you do from day one when you’re locked up until the day you’re released? They are dying to change, to transform.

What we have in our country is an absence of systems of care. They’ve been trying to heal their entire lives. Other people don’t have to believe me. Women are doing this work, and we’re going to keep doing it. No, it is not enough. But doing nothing is not the answer.

Imani: You mentioned her earlier, but I did want to talk about Angela Davis and her book, Are Prisons Obsolete. One of the incarcerated women who she interviewed, Marcia Bunny, said that she did not feel safer in prison, despite being away from her original abusers, because the abuse had not stopped. This book was published 20 years ago now. What, if anything, has changed in that time that you’ve noticed? And if you were to dream big, what kinds of nationwide policies or initiatives would you put in place to better the lives of Black women who are incarcerated?

Biggs: Sadly, in that time, the number of women behind bars has continued to skyrocket because we continue to target low-income Black women, and increasingly, we see undocumented Latina women as a part of the nationwide prison population as well. Why is that? Because we refuse to do things that are proven to work and to allow folks who have lived on both sides of the prison door to be at the seat of the table for those conversations about what is needed and what works. So yeah, I don’t have a magic wand. But some things that I think do need to happen is to stop taking what police and prosecutors say as the truth. There are many people behind bars who have done no harm to anyone but themselves, or they’ve shoplifted some diapers from Target, and now they’re going to serve 30 years when Target isn’t really harmed. Oftentimes, what people want more than anything else as victims of violence, neglect, or other kinds of harm, is recognition and an apology, and they want to be part of a conversation and an accountability process. We have the resources to be able to try a zillion new things and to try to support people in holding one another accountable when harm does occur.

What we have unfortunately done is outsourced that responsibility for individual care and accountability toward judges and police, especially since the end of the Civil War. As the number of police officers rises, we need to take money from policing and put it into the kinds of accountability processes and support that are actually effective. Most people who do the worst harm are not in prison. We, unfortunately, have been convinced that the boogiemen out there, the super predators, are “bad” women who are “crack hoes and bitches.” In this case, “they don’t need help.” They are “too dangerous.” And so we have allowed hyper-militarized police and prosecutors to do that work for us. We need to reallocate resources away from that.

In the meantime, if people can trust that we know how to hold one another accountable, and to do it…wow, the magic that could happen. If we can undo some of the worst practices and thinking about patriarchy, oh, the magic that we could do in the world. I think that needs to happen across institutions, families, churches, music, song, dance, everything. But I think that in the end, the biggest thing is to stop believing the single story that we cannot hold each other accountable when harm occurs.

Along with all that, I guess we also have to ensure that people have decent housing. The COVID-19 pandemic teaches us that we actually can provide people with housing if we just commit to doing it. We can eliminate barriers to public health, too—to mental health, and to care. Our elected officials, they’re always late to the party. If we want other ways of being in the world, then we need to build them ourselves. That doesn’t mean fundraising first. Most conflicts get handled between people without money involved. And storytelling is a critical component of shifting the narrative.

There is a role for artists in this, absolutely. We need to open up and invest in and believe in the possibility of the human and to bring us all into the fold in much more generous, generative, powerful ways. These criminalized black women who I have worked with, incarcerated artists, have stepped up to the plate in ways that a lot of free people have refused to do, are afraid to do, or consistently shut down. Or, are just simply unable or unwilling to do. And so, my book is really about honoring these women.