When I was a child growing up in Charlestown, Rhode Island, I was surrounded by artists but I didn’t realize it. As a student in the Chariho School District, the art being created around me did not look like the art in my textbooks. The Greek pottery we spent a semester drawing in detail was considered superior to the traditional pottery that sat on my shelves at home, etched with simplistic geometric patterns or impressed with scallop shells. The designs woven into medieval tapestries were venerated far beyond our finger woven sashes. The stone walls and fireplaces my Grandfather and Uncles built were not revered; the architecture of Rome was. So much of the art that encircled me was omitted from my early education. Yet each and every creation of my community told a rich story of ingenuity, industry, beauty, and survival.

Public school systems are an entry point to the global art world. Art history, lessons in perspective, explorations of textures, and field trips to museums all introduce us to various art mediums. But Indigenous students rarely—if ever—see art reflective of our communities appreciated in the classroom. Discouragingly, when they are, they can often be minimized or even be offensive versions of our dearly held traditions. Art teachers may not have the education or experience to respectfully engage students with Indigenous art forms. Some fear incorrectly representing artistic expressions outside of their own cultural experience, and so avoid it altogether. This experience can leave us questioning where we, as Indigenous people, fit in the world of art.

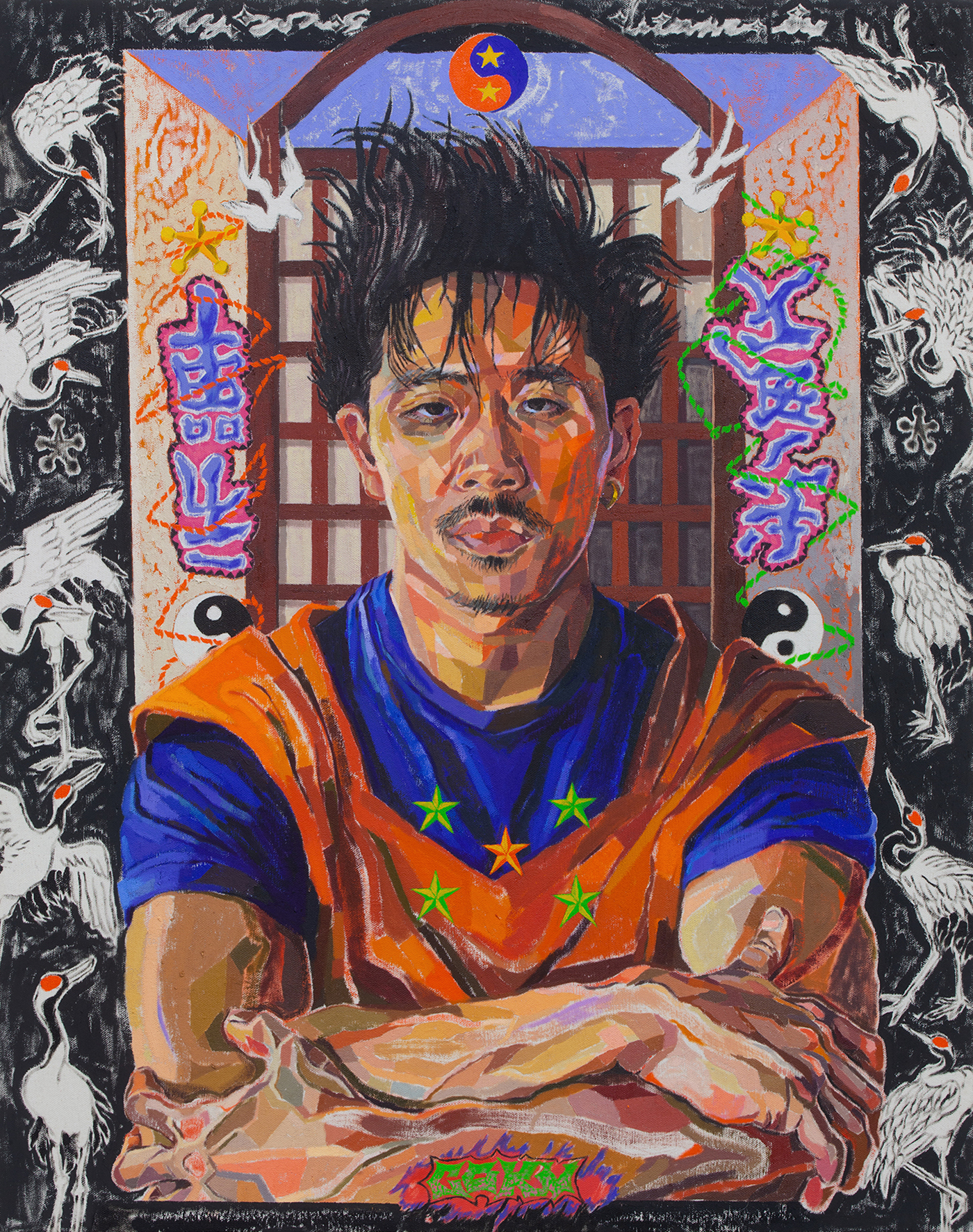

Indigenous artistic expression is often relegated to “folk art.” I find this to be a very othering and disrespectful term. There is a hierarchy in the way art is taught. When one learns about fine art, Indigenous artists are not included amongst the “masters.” Indigenous art is a subset in the art world because much of our traditional arts are practical in nature, functioning as useful items; technology made beautiful. The result of this othering categorization is that Indigenous youth are indirectly being taught that their art is less valuable. The commercialization of art only exacerbates this perception. Indigenous art has continuously been highly undervalued in the arts market. The lack of education around the knowledge, skill and sourced materials required for many Indigenous art forms leads to a devaluation of the expression. Historically categorized as primitive and naturalistic, these words simplify what is in fact a very intricate and often intensive process of creation. Not to mention that Indigenous art is continuously growing and changing. We are a living people—vibrant, thriving, and ever-evolving. There is no category for Indigenous art, no box to contain us. We refuse to be limited or defined by others’ standards.

Trekking through the swamps in search of black ash trees for traditional splint basketry is a challenge in more ways than one. These trees, prized for their strength, durability, and malleability, have become increasingly difficult to locate in our region. The dispossession of land has left Indigenous people with limited areas for sourcing materials. This is further exacerbated by invasive species like the Emerald ash borer, a beetle native to Asia that is responsible for the destruction of tens of millions of ash trees in over 30 states. These cherished trees are at the heart of many Indigenous conservation and restorative projects. Accessing materials is just the first challenge in the lengthy and tedious process of basket making. Pounding and splitting, smoothing and dyeing, there were so many steps to prepare the materials before the weaving can even begin. A single basket traditionally sourced and fabricated by a skilled artist can take upwards of a week or more to complete from start to finish. Yet these baskets can sell for as little as $50.

Flat reed splint basket with stamped designs, Silvermoon LaRose, ca. 2016.

Courtesy of the artist.This is why inclusive art education is so important. We should be expanding arts education to include a heterogeneous collection of voices. We should revel in the varied perspectives and contrastive expressions of others. We should offer insight into the impact environmental challenges, climate change, and threats to natural resources have on various cultural arts globally. We can expand our worldview by engaging with a diversity of creative expression and challenges. Unfortunately, our society tends to regard art as optional. It is offered as an elective in the school systems, and is the first on the chopping block when budget cuts are made. If one is to engage deeply in the arts, it is often as an extracurricular activity. In Rhode Island, there are a plethora of art related programming for young people, but there are significant inequalities in these offerings. Programs that are little to no cost are concentrated in urban communities. For rural communities, these programs can be extremely costly and often exclude marginalized students. According to the 2021 Rhode Island Kids Count, 55% of Native American children were living in poverty, the highest of any demographic. Extracurricular art activities become a privilege denied to those who cannot afford them.

I don’t want to feel defeated by these challenges. I want to feel inspired and motivated to create change. Every child should experience the freedom of expression through art. Every child should feel valued and appreciated. Every child should feel emboldened to create. Every child should feel that art is attainable.

Yòh (four), acrylic on canvas, Silvermoon LaRose, ca. 2022.

Courtesy of the artist.I wrote the following when I was thinking about how I felt about art growing up in Charlestown, Rhode Island. I wish I had known the artist that was always inside of me, but when I was young, art always felt so unreachable.

I don’t know anything about art. We make macaroni crafts and paper mache in my elementary school. The best projects are displayed in the cases on the walls along the school hallway. My work has never shone. It gets packed up at the end of each quarter in a portfolio we made out of scrap pieces of poster board. I take it home and store it in a box under my bed. Mediocrity is not celebrated. Art is unreachable.

I don’t know anything about art. If you’re good at it, you can go to a special art school where they will teach you to be even better. Who gets to decide if you’re good enough? How do they know if you’re getting better? Maybe there’s a standardized test that can show all that, schools really like tests. I guess it doesn’t really matter. Mom says that school costs more per semester than she makes in a whole year. Art is unreachable.

I don’t know anything about art. I hear there is art hanging in museums and galleries, whatever those are. Grand buildings with pillars and fleur de lis, whatever those are. There’s lots of pictures by dead painters preserved in gold gilt frames and people pay $24 to look at them. I don’t think we have any museums and galleries here, just turf farms with no fleur de lis. And I don’t have $24. Art is unreachable.

I don’t know anything about art. I heard art is an elective. That means it’s not a necessity. So if the school doesn’t have the money, they can take it away. At the school budget meeting they fought over it. Some said kids need access to art to help our brains develop, to expand our worldview, to stimulate creative thinking because that helps us learn better. They said all kids should have access to art. I wondered if I ever had access. Others argued that there’s art programs all over the state and some of them are even free, but none of the free ones are down here where we live. They say if they cut art, kids will still have access. I won’t. My parents can’t afford to pay for it and I don’t have a ride to Providence. It seems that when art is an elective, it becomes a privilege. Not all of us are privileged. Art is unreachable.