I started my series, High Interrogation, two years ago to overcome what felt like an inability to endure after experiencing a traumatic bodily event at the hands of a white man. In October of 2020, a known and previously imprisoned sexual abuser followed me throughout Providence in an attempt to do who knows what. The possibilities of what could’ve happened left me shaken, angry, and depressed. My work became about those feelings, what this white man did, and what informed his actions.

“Why would a white man think he could just grab, force, and control me as he wants?”

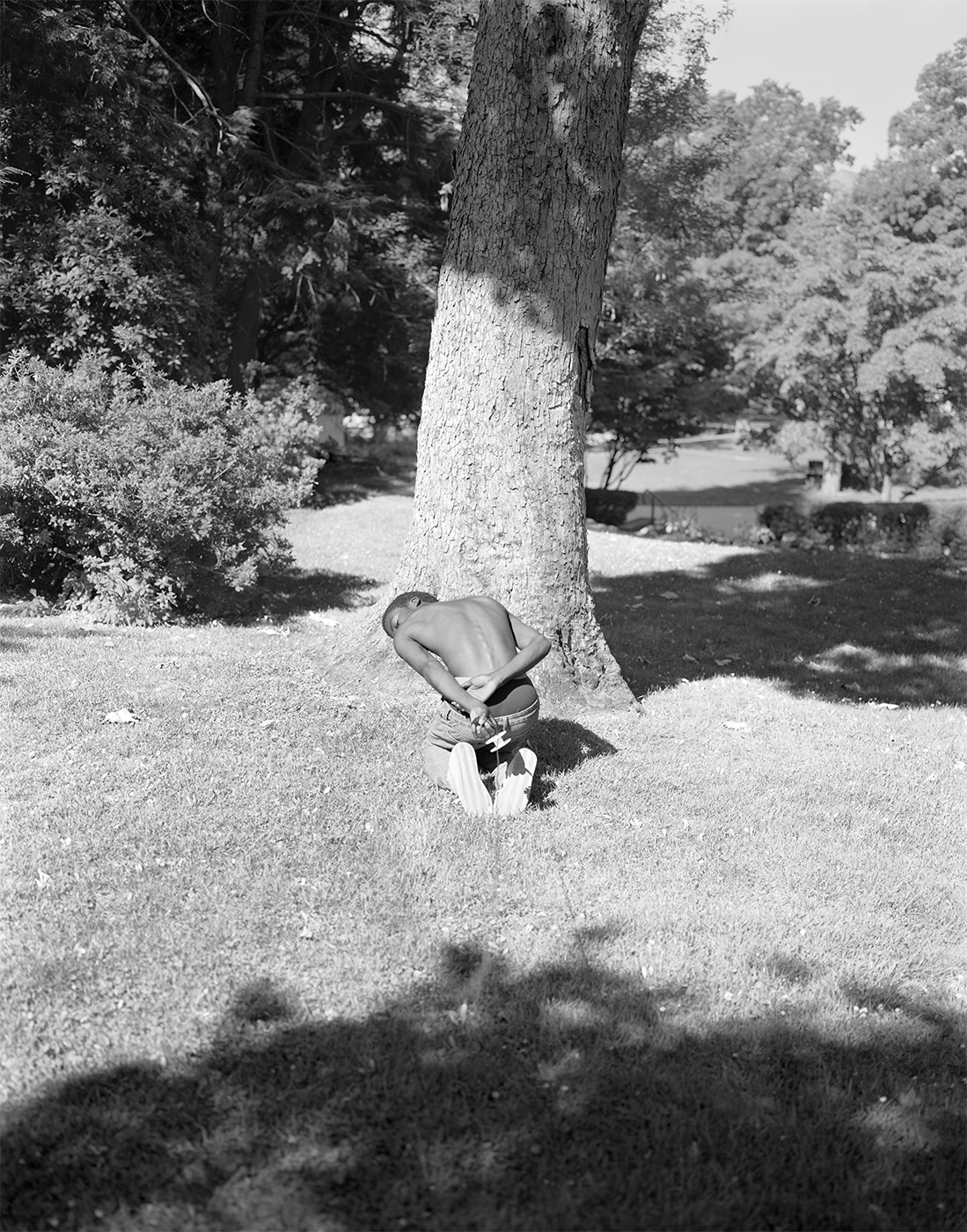

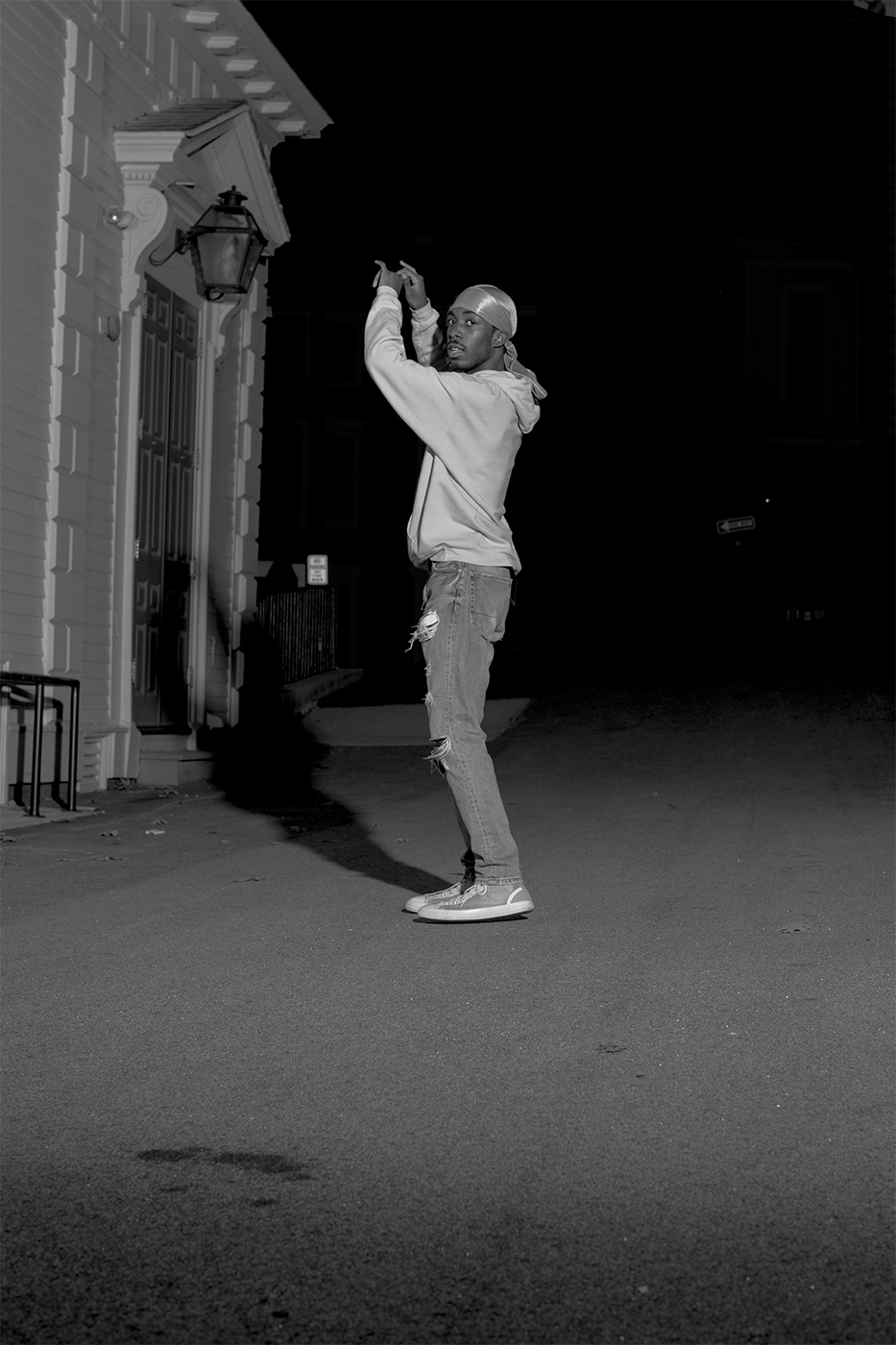

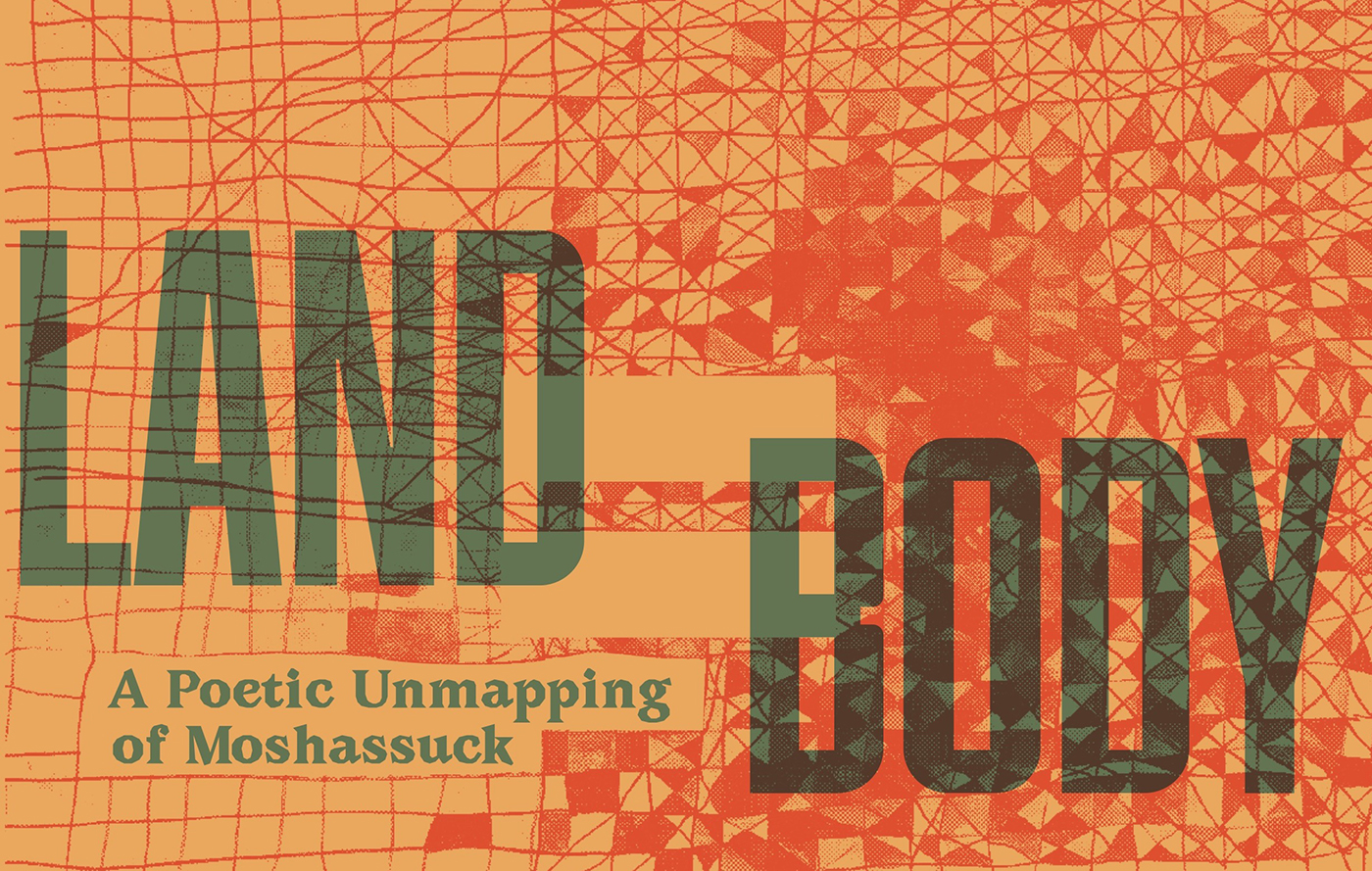

I began to create images that gave me perspective on where I stood in life, opening the doors to a practice committed to unraveling my understanding of how that traumatic experience still rests inside of me and is connected to histories of other brown bodies in America. I write, think, and wonder about living, trauma, and experience and how they intersect under the lenses of gender and race. Through experimental image-making, I create expressive languages for what feels like the unexplainable and omnipresent forces of the transformed presence of white supremacy. I use my body to engage in performative gestures and regain power and agency to act in retaliation against my history, or to understand my relationship with the histories of the land I walk that holds stories like mine.

Making images allows me to display the rawness of my ability to move through the day, or lack thereof, that wouldn’t normally be seen by the public. By bringing people into both my physical and psychological world of fatigue, hope, and depression as it exists in real-time, I can place my world in front of viewers. Turning the lens on myself became a way to show what it looks like for me—a non-binary, black, gay person—to have a newfound agency to define what a life worth living in-progress with so much to unpack can look like. In my practice of making images, it became important to show what happens when I stand in frame as not only an artist but also as an everyday black person who perpetually feels the collapse of their world.

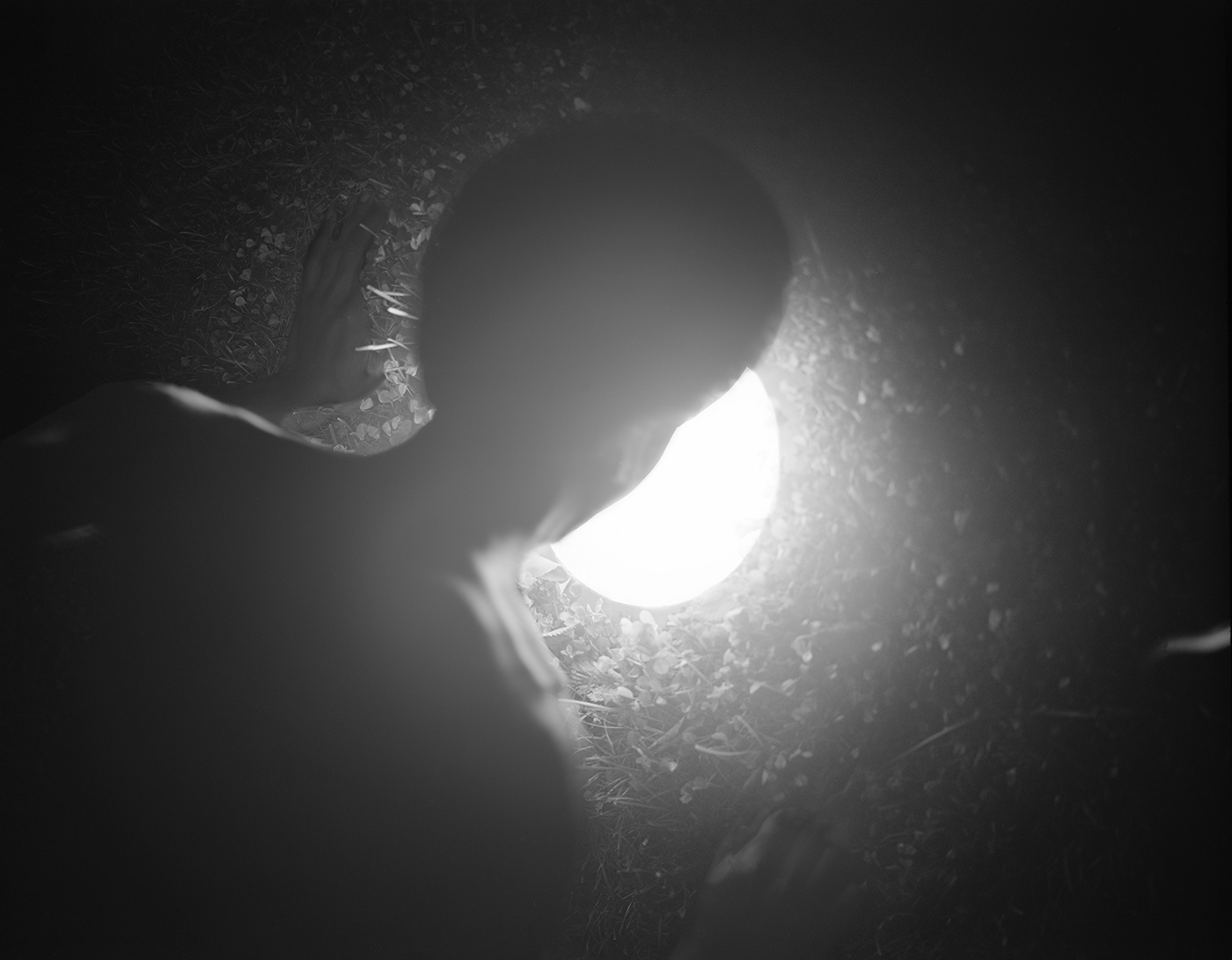

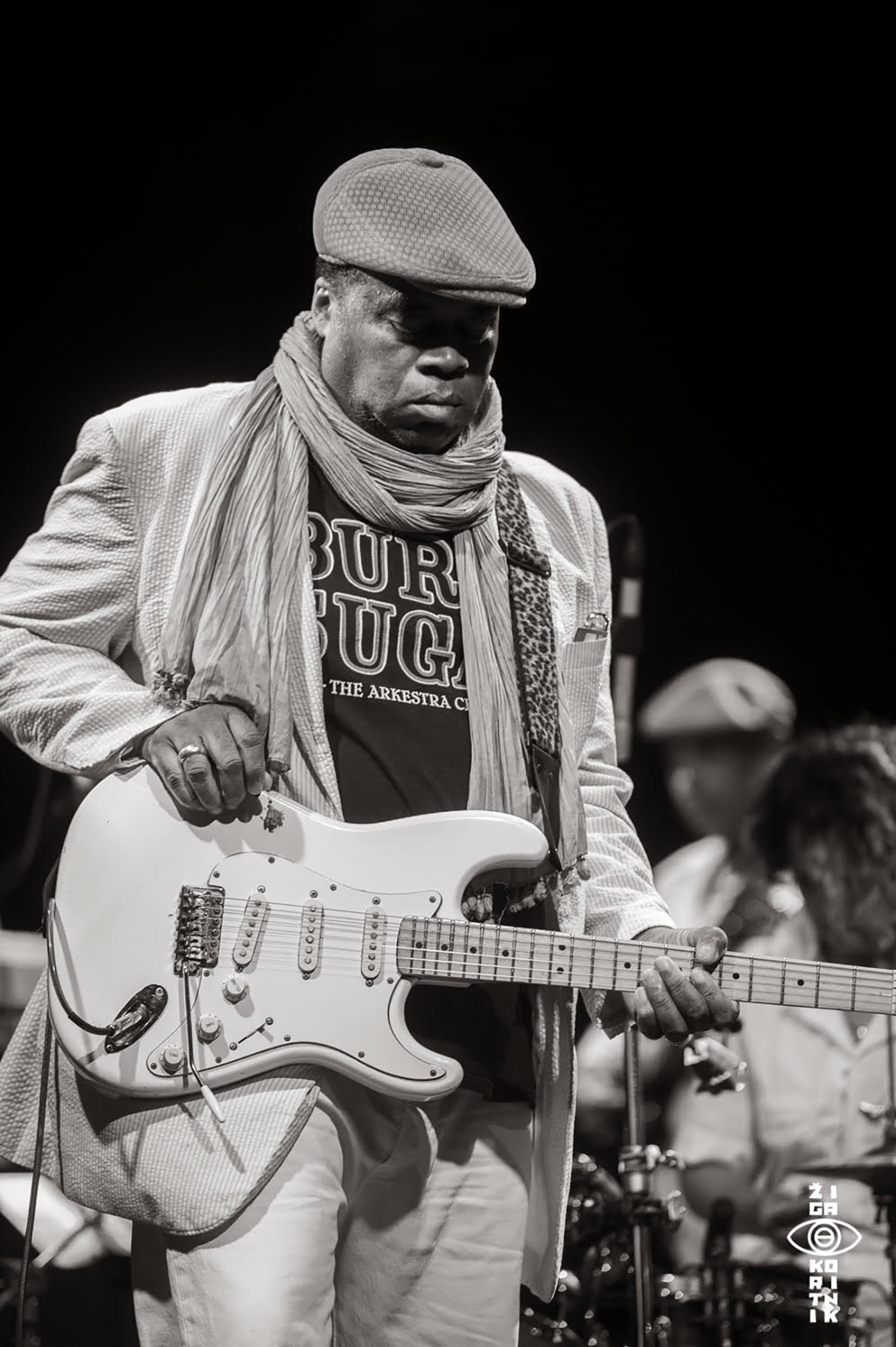

I became interested in film because of its unpredictable nature, extensive process, and the riskiness that comes with working with such a sensitive medium. Most of my images are made using a 4x5 camera. There is no way to breeze through taking a photo when you only have a limited number of exposures. I began to love that film is prone to accidents and how these accidents can alter the image at any point in the process. Most of the scenes that come across as surreal or perplexing in my images occur on the negative. I embrace the use of crumby cable releases and lenses with faulty shutter openings because a lot of the effects translate well into the conceptualization of my images. I experiment with artificial and natural light, endurance, and repetition to imbue my work with a level of theatricality. It is important for me to shed light on the act of defying normativity in my everyday life. This is why I began photographing myself anywhere and everywhere. Maybe if I show how my body behaves, reacts, and expands at the visual cues of the white man and his country, people wouldn’t need to question the pain my black body is in and, instead, they would begin to understand what is causing the pain. Landscapes and institutions hold the histories of the violence enacted upon the brown bodies that have historically stewarded the land where my performances happen. Some of the images I make are a testament to my ability to counteract this violence while others are testaments to my ability to go against that history and display an act of nonconformity.

So, for the person in pain, so incontestably and non-negotiably present is it that ‘having pain’ may come to be thought of as the most vibrant example of what it is to ‘have certainty,’ while for the other person it is so elusive that ‘hearing about pain’ may exist as the primary model of what it is ‘to have doubt.’ Thus pain comes unsharably into our midst as at once that which cannot be denied and that which cannot be confirmed.

I wonder how many people don’t believe me or my pain. I wonder how many times they are going to ask me a question, questions that are ignorant and come from a place of opposition or selfishness. How many times will they create opposition against what I’m trying to say, the help I’m trying to ask for, the perseverance I’m striving for?

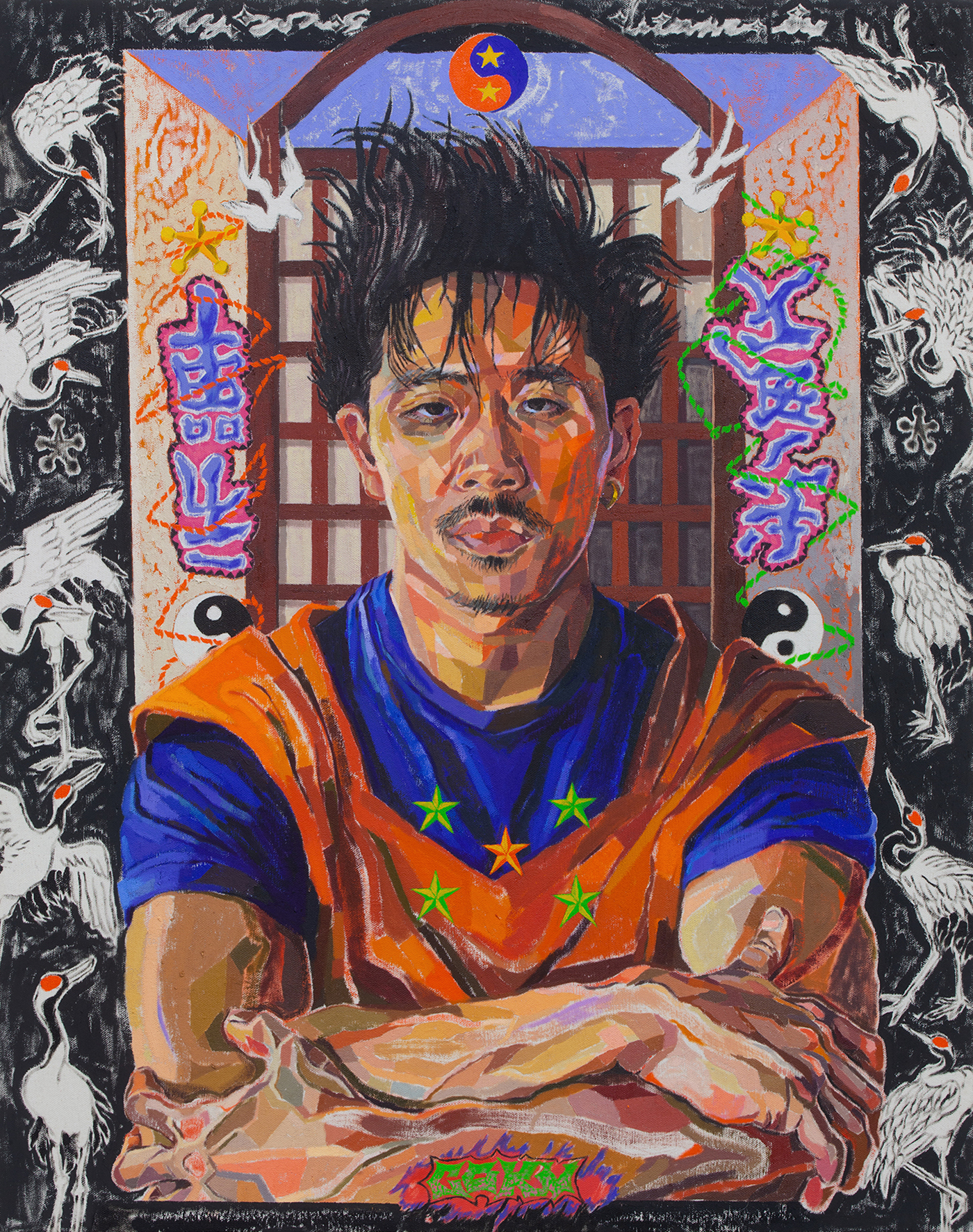

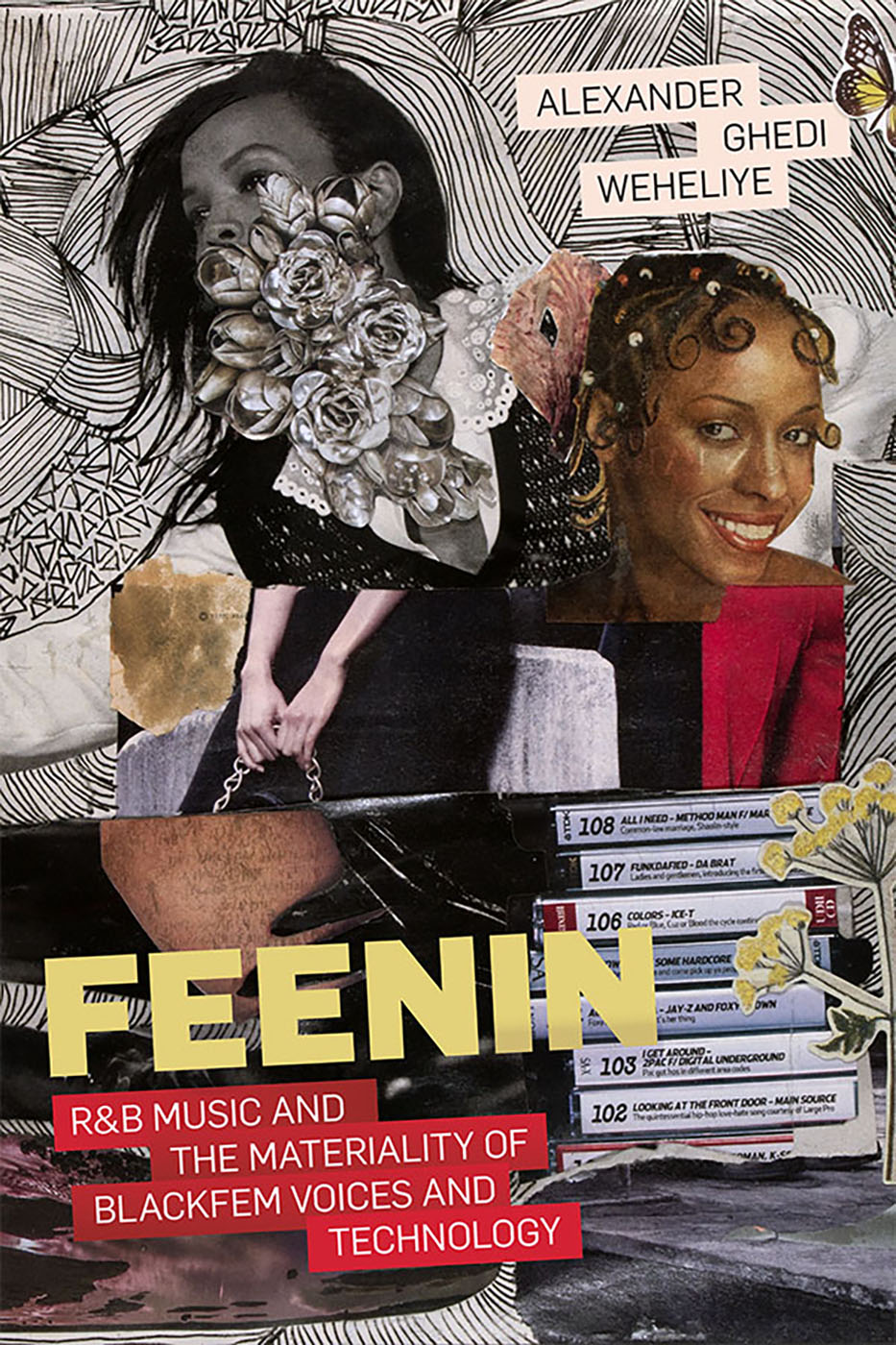

Working on High Interrogation has become more than just a project. It has become my life practice. You can find me constantly obsessing over the photographs of Paul Sepuya, Kerr Cirilo, Anique Jordan, Allie Tsubota, and many more. These artists aren’t afraid to cut through the bullshit and deal with conversations around gender, race, trauma, that directly go against or call out American history and white-washed aesthetics of making. Paul Sepuya’s work challenges traditional notions of the gaze and disrupts established narratives, offering a fresh perspective on contemporary portraiture and the queer experience. Like Sepuya, Kerr Cirilo’s practice uses self-portraiture alongside artifacts of Americana and European culture such as flags, paintings, and landscapes. By placing these signifiers as backdrops, Cirilo consistently becomes the foreground of not only the work, but also the conversation about the effects of imperialism. Allie Tsubota focuses on the history of Asian/American incarceration through time, making photographs as landmarks that reflect on the U.S government tactics that prevent Asian/American roots from being established in American soil through systemic oppression. Anique Jordan’s work spans installation, photography and sculpture, focusing on the social and cultural past of the black body in relation to the communities she comes from. I became fascinated in owning my unique background which has led me to unearthing what lies behind the conception of American identity and history. I’ve learned from these artists that “the self” is a powerful vehicle that leads me into new paths to self discovery that I want to share back with my community.